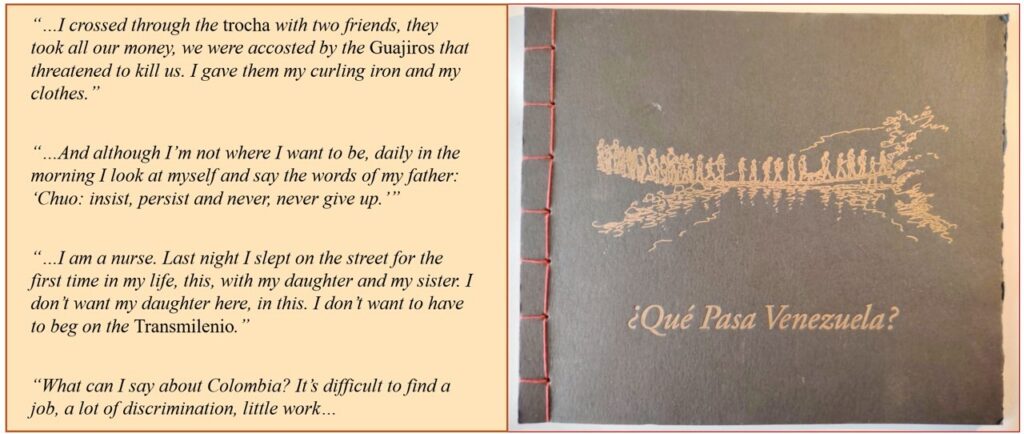

Bogotá, Colombia – “We’d like to hear the story you might tell your friend, your mother, your father, a brother, a sister. It’s important the world hears what is going on, so that your story is not forgotten.”

With these words began hundreds of huddled chats in the crowded shelters dotted along Colombia’s cold mountain routes between its border with Venezuela and the capital Bogotá to the south.

Here were Los Caminantes, ‘the walkers’, thousands upon thousands of Venezuelans trudging the highways, the poorest and least prepared of the 8 million that left their home country following the economic collapse of the previously oil-rich South American country.

The exodus had started a decade ago, in 2016, but accelerated in 2018 among acute shortages of food and medicines and surged again after the COVID-19 pandemic and political crises. Many were escaping hunger and extreme poverty. Others persecution. All had a story to tell.

But as NGOs and U.N. agencies scrambled to assist this slow-moving mass of humanity – with the help of many Colombian communities along the route – Douglas Lyon, a U.S. medical doctor working in Colombia, realized something was missing.

“I’d worked with emergency organizations like Doctors Without Borders and knew the importance of bearing witness to human suffering,” he told Latin America Reports.

“But in the world of humanitarian help we are always rushing from one crisis to another. Seeing the trails of caminantes, their hardships, I realized we needed to record their stories.”

All in it together

From this epiphany was born TodoSomos (“We Are All”) a small NGO dedicated to capturing the human voices in a massive migrant crisis. With a modest group of family and friends, many working as volunteers, Lyon and his team quickly started to visit the roadside shelters in Norte de Santander, the mountainous region of Colombia that for many migrants was the first port of entry.

At peak flow, according to the U.N., more than 5,000 Venezuelans a day were crossing into Colombia. Many had already faced immense hardships crossing their home country, and the dangers of the infamous trochas – clandestine border crossings – where armed gangs stole the last of their money, food and any other valuables they still possessed.

The TodoSomos methodology was deceptively simple; leave notebooks and pens at the overnight shelters where migrants congregated, with perhaps a group chat to explain that anyone was welcome to write their stories, anonymously and with no fear of persecution, but with the goal that one day these stories might be heard.

Lyon believes the writing process had an immediate therapeutic impact, giving voice to a marginalized and mobile community, but also a moment for the caminantes “to organize their thoughts, reflect on the journey, their hopes and plans”.

But he also saw downstream benefits from collecting stories. With his small team of staff, TodoSomos would read through the frequently harrowing testimonies and pick out key themes. This information was collated and condensed into a monthly report sent to NGOs and U.N. agencies, but also fed back to field workers and, at group reading sessions in the shelters, the migrants themselves.

A collection of stories was also published in a small book, “Qué Pasa Venezuela?”

Beyond that, Lyon hoped that TodoSomos could one day preserve the testimonies from this wrenching moment in Latin American history.

The living archive

That became reality last year when Cornell University incorporated 25 ledgers — handwritten in the mountains of Colombia — into its prestigious Rare Documents and Manuscripts Library.

There they form a “living archive”, Irina Troconis, a professor of Latin American studies at the upstate New York university, explained to Latin America Reports.

“This archive collects those of people who are, presumably and hopefully, still alive, which means it is an archive of the present, rather than one from the past,” she said.

The ledgers, available to academic researchers in the library, were of immense value, she said.

“It is a highly diverse record of an unprecedented moment in Venezuelan and in Latin American history, the story of migration told ‘from below’, and, as such, it makes space for everyone, regardless of their political affiliation and socioeconomic background, to say what they have been through.”

Troconis, herself originally from Venezuela, said the stories provided a snapshot of a country “free from the ideological and theoretical frameworks” imposed by outsiders.

“As an academic who has been researching Venezuela for the last 10 years, I have seen how often the country becomes an empty signifier; its reality completely dismissed in the name of a failed political project or violently reduced to a cautionary tale. These stories are a reminder that Venezuelan people are not abstractions, and that their complex realities deserve more than a slogan or a ‘theory’ constructed from the comforts enjoyed by those far away.”

For the professor, who read through many of the 2,000 testimonies, one revelation was the huge range of situations faced by migrants. Whereas the media tended to simplify the crisis with common causes and solutions, the archive revealed a much more complex phenomenon.

“There isn’t a single image or representation of the Venezuelan migrant. The stories reflect an impressive diversity, not just in terms of class and political ideology, but in terms of how each person has experienced the difficult journey,” she said.

The stories were often harrowing, but also full of hope, she said.

“There is near-indescribable pain, and shocking examples of violence, but there is also love and connection, and moments of solidarity that speak of the informal networks of care that are taking shape, and that, for many, are lifesaving. And there is, consistently, a deep desire to go back to Venezuela.”

Back on the road

With recent changes in Venezuela, and the U.S.’s capture and detention of former president Nicolás Maduro in January – now facing trial for drug charges in New York city, not so far from the Cornell archives — that desire could become a reality.

But not a certainty, said Lyon this week: the current political limbo in Caracas left Venezuelans fearing even greater instability, economic decline and deterioration of human rights, with no guarantees when or if the country would move to democratic rule. Venezuelans could return. Or flee.

With this in mind, TodoSomos this month started reactivating story collections in the few Colombian shelters still operating close to the border, working with NGO On the Ground International that runs an overnight shelter in the town of Pamplona.

The shelter had seen a spike in migrants since Maduro’s capture, from 10 a day to more than 60, mostly flowing out of Venezuela, though not on the scale of previous surges.

Shelter support worker Kenny Rojas – himself a former migrant – said many people were travelling with children. They seemed more prepared for the arduous journey compared to previous years.

“They have more information, and have a better route planned,” he said.

Many were people returning to jobs outside of Venezuela, rather than a panic flow. The current uncertainty was causing many people to stand by on both sides of the border.

“I think people are waiting for a transition, and if everything goes well, there will be a very high return flow,” he said.

Clinical approach

So far, the signs are mixed: the old Chavista regime has retained power under interim leader Delcy Rodriguez, though some political detainees have been released.

Conflict experts see risks from mercenary armies such as the ELN, political infighting in Caracas, powerful military leaders embedded in illegal activities — and unlikely to give up their privileges — and support from Washington pivoted on the benefits of the oil trade rather than reform.

For TodoSomos, this was an important moment to be again collecting testimony, said Lyon. The NGO was submitting funding proposals to donors to scale up operations ready for whatever outcome. That could also mean getting stories from within Venezuela.

“We are seeing political and military moves by the three largest global powers to expand their influence and secure scarce resources – oil and minerals. These moves rarely take into consideration their effect on ordinary citizens with meager resources,” said Lyon.

The medical doctor likened the TodoSomos approach to a clinical consultation; the patient’s story, and own interpretation of their ailment, being a key factor in any final treatment.

If Venezuela was the patient, then it was still in the emergency room. Lyon is convinced TodoSomos has a role in any rehabilitation.

“If we listen better, if we are able to find space for both empathy and analysis, we’d do a better job of not only understanding and responding to humanitarian crises – but also preventing them.”

Featured image: Venezuelan migrant family in Norte de Santander, Colombia in 2018.

Photo credit: Steve Hide