Bogotá, Colombia — Colombia continues to speculate over who is behind last week’s assassination attempt of Miguel Uribe Turbay, a Colombian senator and pre-candidate for the 2026 presidential election, gunned down in a public park during a rally in the country’s capital.

The broad-daylight shooting, by a young hitman hired by a local drug gang, left the 39-year-old right-wing politician gravely injured and still in intensive care after life-saving brain surgery.

But even with the immediate detention of the shooter – tackled close to the scene by Uribe’s bodyguards – and two subsequent arrests of suspected accomplices, there are still many questions to answer.

Investigations so far have pointed to an urban drug gang carrying out the attack. But as many Colombians know, such gangs will kill for cash alongside drug dealing and extortion. The hidden sponsors behind such acts can take years to reveal. Or never.

Will the Miguel Uribe case be any different? As political tensions rise, and politicians fear for their lives, many are hoping for a quick resolution.

A walk in the park

Uribe was attacked in the early evening of June 7 while addressing a public rally in a small park in Modelia, a barrio in the west of Bogotá following a walk-about with local Centro Democratic (Democratic Center) supporters.

The senator was a nationally known figure and scion of a political family (his grandfather was president) who, despite his youthful looks, had been in the rough-and-tumble of Colombian and Bogotá politics for many years, and previously an unsuccessful mayoral candidate.

The pre-planned event in the busy high street ended with an impromptu soap-box address – in fact he stood on stacked beer crates — cut short by a barrage of shots from a Glock 9mm pistol wielded by a 14 or 15-year-old would-be assassin, who filtered through the crowd easily avoiding the light security detail supposedly guarding the senator.

Despite his gilded past, Uribe had a reputation as a hard-working politician, loyal to his mentors, and prepared to pound the pavement at street level, pushing his agendas in cafes, local business and mingling with the public, such as Saturday last.

The teen fired to within meters of the candidate and three bullets found their mark: one in the leg and two in the head.

Ambience of violence

Even as Uribe was bundled away bleeding and gravely injured, the shooting sent shockwaves through the Colombian political establishment and rocked a capital city where political assassinations – or attempts – were seen as a thing of the past.

“We’re going back thirty-five years”, was a refrain heard around Bogotá last week with echoes of the dark days of a drug cartel’s’ war on the Colombian state and extermination campaigns by paramilitaries that saw dozens of mostly left-wing politicians injured or killed.

Tragically, Miguel Uribe’s own mother, journalist Diana Turbay, was killed in 1991 after being kidnapped by Pablo Escobar’s Medellin Cartel as part of his all-out war to end extradition of drug kingpins to the United States. The event is recounted in Gabriel Garcia Márquez’s ‘News of a Kidnapping’.

Journalist Vicky Dávila, herself a presidential candidate, was quick to blame incumbent President Gustavo Petro as responsible, in spirit if not deed.

“Petro has promoted an ambience of violence,” she announced from outside the hospital where the victim was in intensive care, without providing any factual link between the Colombian mandate and the events in Modelia.

The U.S. Secretary of State found common ground with Dávila: “It’s the result of leftist rhetoric,” asserted Marco Rubio, calling on Petro to “temper his incendiary rhetoric.”

Who benefits?

In another scenario presented by left-leaning former Medellín mayor Daniel Quintero – again providing no evidence – he blamed criminal group Clan del Golfo (also known as the Ejército Gaitanista de Colombia or EGC), itself born out of assassination squads, for trying to kill Uribe as part of a plot with “an extreme right group, along with a foreign country, to destabilize the government”.

Quintero followed this cui bono – who benefits? – line of thinking to turn the blame back on Vicky Dávila herself: she would benefit by getting fellow right-wing rival Miguel Uribe “out of the way” while bringing Petro into disrepute, he conjectured.

Dávila herself then pivoted from Petro to blaming Iván Mordisco, commander of FARC dissident group Estado Mayor Central or Central General Staff (EMC), as part of a “terrorist operation” against right-wing politicians, herself included.

But Mordisco is just one of many suspected warlords, gang bosses and guerrilla comandantes who could benefit from sowing the seeds of political chaos by killing a candidate.

The problem in Colombia is not a lack of suspects, rather a surplus.

Pointing to “The Pot”

Some facts are emerging. First, that the teenage gunman had been hired to pull the trigger, a common scenario in the Colombian underworld.

“I did it for the money, to help my family,” shouted the gunman as he was pinned to the ground by bodyguards who captured him shortly after fleeing the park, in a scene captured on many phones by many bystanders.

He also yelled out he was hired by “la olla” or “the pot”, Colombian street slang for local drug outlets, and could “give numbers”, presumably meaning the phone numbers of his contractors.

The would-be assassin was briefly hospitalized for a leg wound then put in protective custody, accused of attempted murder and possession of an illegal gun.

According to information released by official state investigators, the teen later confessed he had been contracted for 20 million pesos (US$5,000) by three suspicious persons – two men and a woman — spotted on CCTV cameras with the shooter in a small grey car in the hours leading up to the attack.

The Caquetá connection

In the days following the shooting, the grey car was stopped at a roadblock in the south of Bogotá, and the driver apprehended. Local media reported that driver was Carlos Mora, a 27-year-old who gave an address from Florencia, Caquetá, who judicial sources told newspaper El Tiempo was linked to “networks of hired killers outsourced by criminal gangs and armed groups”.

In fact, according to judicial documents, Mora had been arrested before in Florencia in September 2024 and charged with transporting military-grade weapons and ammunition, supposedly on behalf of one of the armed groups that thrive in the region.

Official investigators also reported that Mora and the grey car had been seen on cameras in Modelia on June 5, just two days before the attack, confirming the suspicion that the hit was preplanned, and Mora was a key organizer.

Then, on June 14 investigators announced the capture in Florencia of 19-year-old Katerine Martínez, alias “Gabriela,” suspected of being the person seen on CCTV cameras in Modelia with Mora and the teen on the day of the shooting. She was flown to Bogotá this weekend for questioning.

The fourth suspect seen on street cameras, which Mora and the teen referred to by his nickname “El Costeño” – a fairly common nickname in Colombia – is still at large.

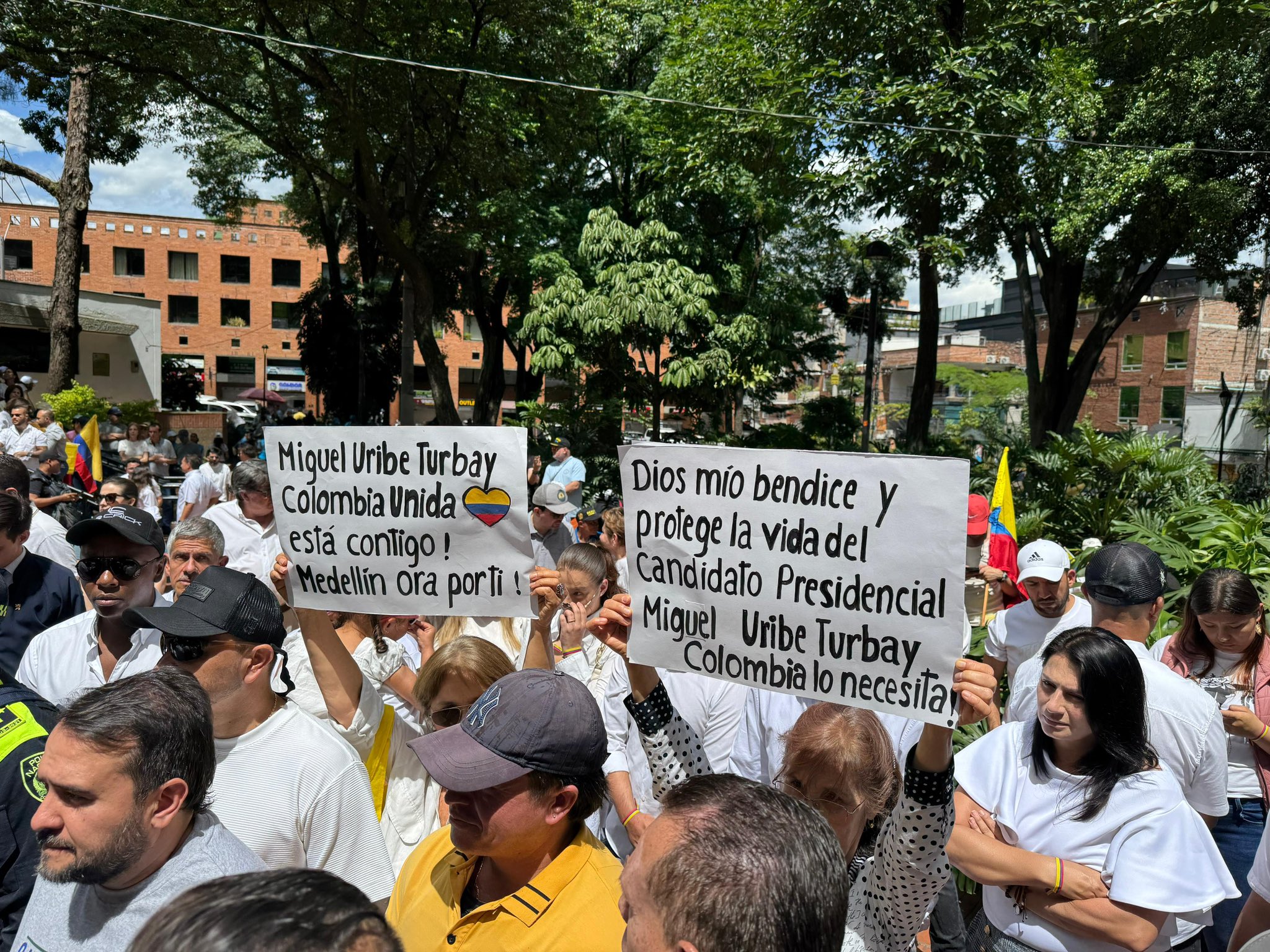

March of Silence

Will these arrests calm nerves in the capital? Unlikely.

Marches to support the stricken senator held across Colombia this weekend called for “fraternity, union and respect for life”, and ostensibly shunned political messaging. But in Bogotá at least, some marches included calls to oust Petro.

While La Marcha de Silencio was peaceful, with an estimated 70,000 gathering in Bogotá’s Plaza Bolivar, some placards read “Petro’s words kill”, or “Petro, out”.

Petro, who has strongly condemned the attack on Uribe, and initially shown support for the march, said that participants had been tricked into a politically polarized event.

“Marchers in Bogotá, Medellín, and Cali did it for peace and the life of Senator Miguel Uribe. Were we deceived?” he tweeted after the event.

“The Colombian people want peace, zero deaths, a referendum, and rights and freedoms. So, if today’s march was a hoax, let’s take to the streets.”

Violence on the move

Petro’s call to counteraction highlights an uncomfortable truth for Colombia; that contrary to a narrative that political violence has diminished since the 1980 and 90s – when at least nine senior political leaders were gunned down, mostly in or around Bogotá – the attacks have simply shifted to less-visible rural areas where, according to figures from think tank Indepaz, 74 local politicians were assassinated between 2016 and 2024, mostly municipal councilors.

“The violence never disappeared, only mutated,” announced Indepaz director Leonardo González after the Uribe shooting. “We demand real conditions of security and participation for those who engage in politics from the margins.”

The situation is equally grim for community leaders and social activists, of whom 71 have been murdered in the first five months of 2025, continuing a blight that in most countries would create a storm of headlines but in Colombia is barely reported.

The country could now face a double whammy of a magnicide threat on top of the persistent killings of community organizers.

Counting on chaos

This scenario plays to public fears that Petro’s government has dropped the ball in terms of security, with his largely failed Total Peace plan and ill-advised ceasefires which have strengthened armed groups since his term started in 2022.

Petro has belatedly started to push back militarily against the major armed groups, including the ELN, FARC dissidents and EGC, though now with a higher hill to climb, while undercutting their finances with high tonnage drug busts.

With some smaller dissident groups, he has continued negotiations even while putting their capos under threat of extradition to the United States.

This does have echoes of the 1980s and 90s when the Colombian state went to war with the drug cartels with dire consequences. Only now the stakes are higher: in 1990 the country had 40,000 hectares of coca plants and now counts on 253,000 hectares, according to United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) figures from 2023.

The illicit economy relies on keeping swathes of the country in low-level conflict, and a central state that knows when to back down.

In June, organized armed groups were striking with car bombs and armed attacks at state targets – with civilian collateral damage – across southwest Colombia.

The Bogotá shooting likely has its roots in the murky intersection of armed groups, gangs and Colombia’s corrosive cocaine industry that thrives on political instability.

Slow wheels of justice

So far, the investigation follows a familiar pattern in Colombia where low-level perpetrators are quickly caught while the intellectual authors are more elusive. Will it go higher?

State attorney’s office detectives have ringfenced their investigation from government interference, and Uribe’s family lawyers have proclaimed a shadow investigation which may – or may not – confirm the state’s findings.

In another twist, this week the family’s investigating lawyer Victór Mosquera announced he had himself received death threats after collecting “abundant evidence” which he was handing over to state investigators.

Everyone’s hoping for a quick resolution but not holding their breath. Only last week, after 26 years, the Colombian state declared its responsibility in the 1999 murder on Bogotá’s streets of beloved journalist and comedian Jaime Garzón, whose whacky TV show Quac El Noticiero kept the nation smiling at his serious investigations.

Garzón was gunned down by killers ordered by senior state officials, but according to the announcement last week, “Colombian justice has not been able to convict the entire criminal network that participated in the crime.”

Not so soft target

The question remains: why Miguel Uribe? The senator was well-known and respected but not considered a front runner for the 2026 presidential election.

But with his penchant for public walkabouts and, on the evening of June 7, in Modelia, a reduced security detail (for cost-cutting reasons he was down to a handful of guards), he could have been seen as an easy target for the amateurish would-be assassins lying in wait.

Though as it turns out, not so soft. The senator’s almost miraculous survival of two headshots at close range left him in a critical but stable condition a week after the event, and a country on tenterhooks to see if and how he survives. Early this week, Uribe was rushed into a second emergency surgery after a brain bleed.

“Miguel, Colombia awaits you,” was a common refrain at Sunday’s march, printed on banners and T-shirts.

The next month could be critical for both the stricken senator and a divided nation, of which some citizens might now see him as their best hope.

Featured image: Supporters of Miguel Uribe. Image credit: Centro Democratico via X.