Guarulhos, Brazil – They left behind dreams, family members, their possessions — everything they knew. For nearly 100 Afghan refugees camping out in São Paulo’s international airport, the only thing they have are a few articles of clothing and a lot of hope.

Data from the United Nations Refugee Agency (UNHCR) show that since the Taliban’s takeover of Kabul in August 2021, more than 2.7 million Afghans have fled the country — some escaping the oppressive regime, others fearing retribution for their years working with the United States military.

Thousands of those refugees have made the long journey to Brazil, which began offering humanitarian visas to Afghans in September 2021.

On paper, the two-year visa allows refugees to work in the country, and it also provides access to public health, education and social assistance services.

In practice, however, the Brazilian government is having trouble receiving and properly caring for many Afghans once they arrive in the country.

Nowhere is the result of the government’s lack of organization more visible than on the mezzanine of Terminal 2 at the Governor André Franco Montoro International Airport that serves the city of São Paulo.

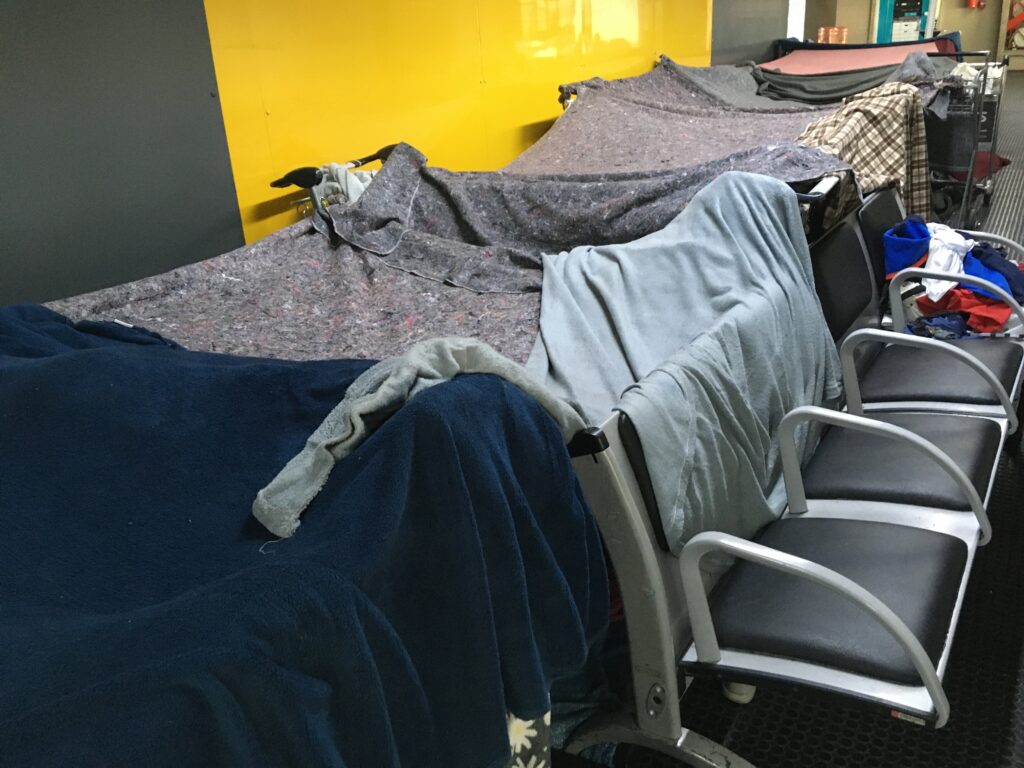

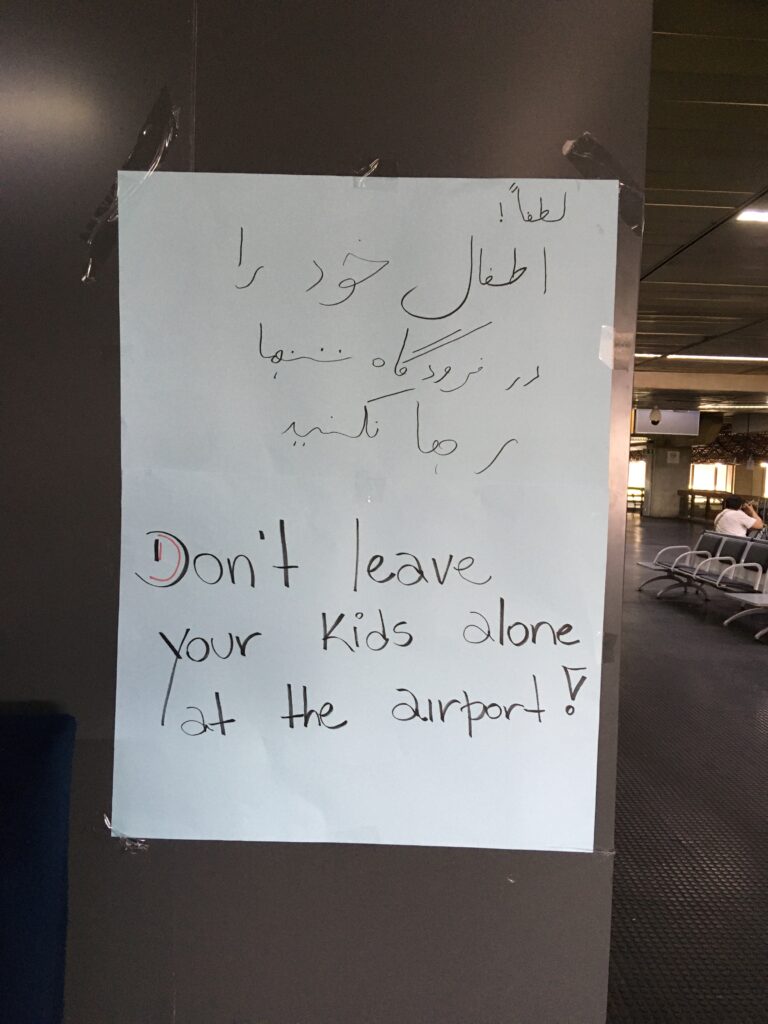

According to information provided to Brazil Reports by the city of Guarulhos, where the airport is located, 99 Afghans are currently living in a makeshift camp near the check-in area in Terminal 2. Sheets, blankets and towels have been formed into improvised tents, providing little privacy for these refugees as travellers mull about the terminal.

Brazil Reports visited the camp on December 22, just days before Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva took office as Brazil’s new president. We spoke with refugees, NGOs and government officials to learn more about the current status of Afghan refugees in Brazil.

Life in an airport terminal

“It started little by little, in August, they arrived and slept in the lobby, because they had nowhere to stay since the shelters were full,” said Lucas Pirez, a photographer and volunteer with the Afghan Front Collective, an NGO that provides food, water and other assistance to the refugees.

In November, according to the NGO, as many as 253 people were camping out in the airport.

Guarulhos, a city with a population of 1.3 million, has just 77 shelters which can house Afghan refugees, according to a statement sent to this reporter from the city.

Thirteen miles away, São Paulo, Brazil’s largest city, has more shelter space. According to information provided by the city’s communications office, São Paulo is currently housing 225 Afghans in reception centers, including 84 refugees who left the airport for shelters during the last two weeks of December.

In total, the United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR) reports that Brazil had registered over 3,000 Afghan citizens in 2022.

There are no showers available to the refugees inside the airport, so volunteers shuttle people to a nearby hotel that has opened its facilities for them to wash up.

A team of medical professionals contracted by Guarulhos visit refugees once a week to provide medical care, including consultations, medicine and vaccines against Covid-19, polio, measles, mumps and rubella. The city also said it provides refugees with daily meals, blankets and other basic items.

In a narrow corridor, separated from the tents by a short walk, there is a kind of warehouse. At the entrance, some bread, water and juice sit on a table — everything donated.

Faadi, a pseudonym for a 21-year-old business administration student at the University of Kabul whose name we’re withholding for security concerns, was serving food to other refugees when he invited me over to chat.

Skinny and about 5 feet 7 inches tall, Faadi had left Afghanistan with 10 of his family members, selling their house and cars and spending their savings to go to Iran, and later to Brazil.

He’d been living in the airport for two weeks and confessed that simple tasks like brushing his teeth or taking a shower had become challenging obstacles. He told me he hadn’t had a shower in 15 days.

“I really would love to live in Afghanistan, but right now we don’t have any choice,” he said. “There is no safe place for us. I would like to return to Afghanistan when there is safety and security for everyone — men, women, babies, girls, for everyone.”

For now, all he asks is for the Brazilian authorities to help find a home for him and his family to restart their lives together in Brazil.

“At that time we did not think that the Taliban would take control of the whole country. We thought that it was impossible,” said Ebrahim, a pseudonym for a 26-year-old man whose name we’re withholding for security concerns.

In Afghanistan, Ebrahim worked as a martial arts instructor for the country’s military and fled to Iran just days after the Taliban took control of Kabul. He sold his car in Iran to afford the journey to Brazil, and has been living in the airport since November.

“The Brazilian Government helped the Afghan people in a difficult situation. We are very grateful to the Brazilian government for granting humanitarian visas to the Afghans,” he said.

Transitioning to Brazilian society

Accompanying local officials and other volunteer groups is the UN’s refugee agency, UNHCR.

The agency relies on partner organizations to help integrate refugees into Brazilian society. Among the services offered by these partners are legal assistance, help with issuing documents, support finding work, as well as Portuguese language classes.

“UNHCR works to complement government services in order to better insert [Afghan refugees] into Brazilian society, guaranteeing their protection and the effectiveness of their integration here in Brazil so that they can in fact rebuild their lives,” Joana Lopes, a UNHCR protection assistant working at the airport, told Brazil Reports.

According to Lopes, UNHCR also helps to partially finance some shelters with its own resources.

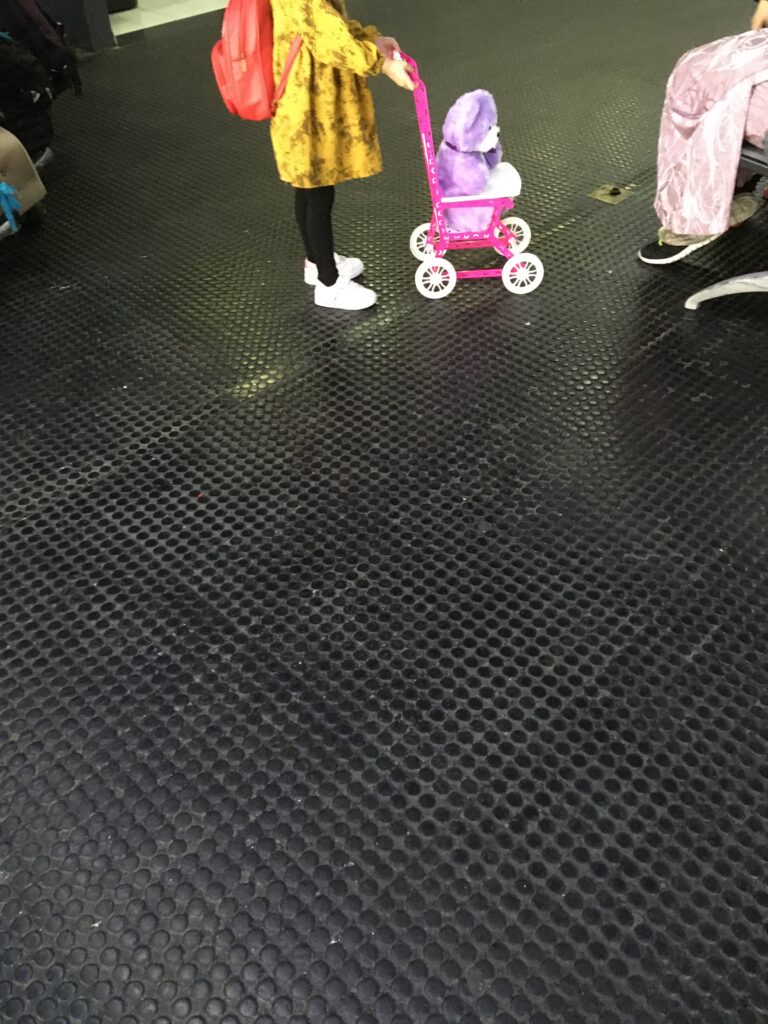

The top priority is to first relocate families with elderly people, children and pregnant women. Even then, the wait can be up to two weeks.

In the case of single men, considered the last in line, it can take over a month for a space to become available in a shelter.

Lopes ended her brief chat with me to take a family of six — which included two small children and an elderly couple — to a local shelter. From across the room you could see their eyes light up and smiles of relief appear on their faces.

The government’s response

On December 22, nine days before the new government took charge, Brazil Reports contacted the Ministry of Foreign Affairs for a comment on the status of the Afghan refugees camping out in São Paulo’s airport.

The ministry responded, saying it was following the case closely and that since April of last year, 6,302 humanitarian visas have been granted to Afghan citizens.

They also emphasized that it is not the ministry’s responsibility to formulate or implement public policies for the reception of refugees in Brazil, but even so, they have taken the initiative to promote articulation between government agencies, international agencies and civil society organizations, with the aim of finding solutions for the reception of refugees.

The ministry added that they work to ensure the refugees’ right to work and access public health services, social assistance, education and other services.

Despite the challenges they face in the country, one thing is certain for Ebrahim: He cannot go back to Afghanistan anytime soon.

“The Afghanistan situation is too bad. We cannot stay in Afghanistan, it’s dangerous for us,” he said.

“We want to work in Brazil, we want to stay in Brazil.”