São Paulo, Brazil – Following two deadly attacks on schools in 10 days, Brazil’s government created a task force to combat school violence that is largely focused on preventing threats by monitoring internet communications, including social media — a move which could potentially impact how social media platforms are regulated down the road.

Two weeks into its operations, and with no set deadline to end, the so-called “safe school operation” task force has already requested the suspension or exclusion of 756 social media profiles that have allegedly promoted hate speech, in addition to 300 requests for platforms including Facebook and Twitter to provide data related to specific accounts.

According to Justice Minister Flávio Dino, the focus on the internet is essential to prevent new attacks, and he denied that monitoring social media goes against freedom of speech.

“The idea that monitoring and regulating the internet is contrary to freedom of speech is false. On the contrary, it is only possible to preserve freedom of speech by regulating, so that it is not exercised in an abusive way,” said the minister.

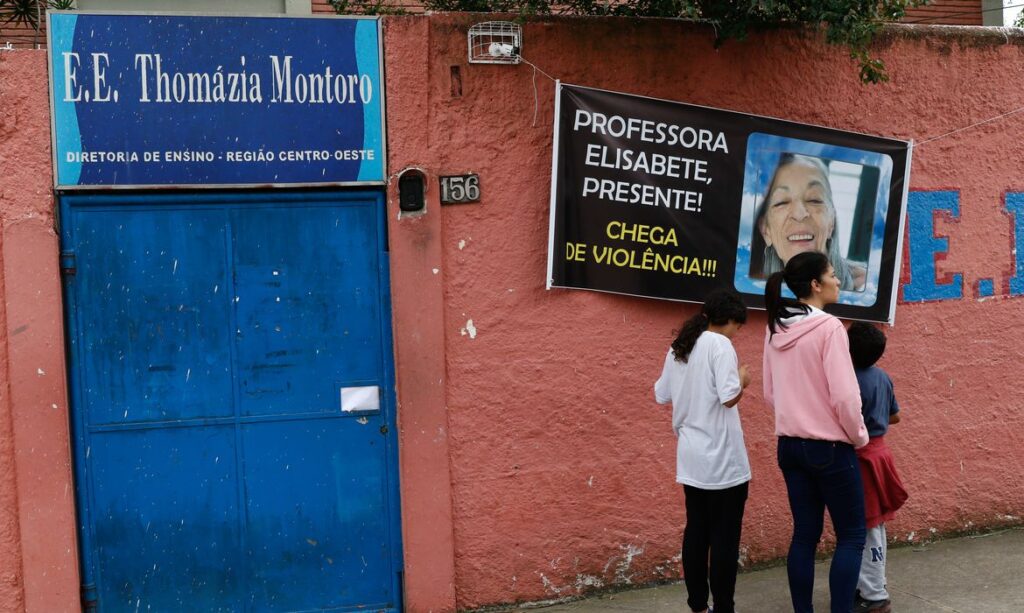

Read more: Teenager kills teacher, wounds 4 others in São Paulo school knife attack

According to Dino, the focus of the monitoring isn’t on the deep web or clandestine forums, rather on social media and websites that are popular with young people. There are at least 160 police officers working exclusively on monitoring, and the minister said that some digital platforms have been collaborating and speaking with the government about the initiative.

President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva said that there is a lot of violent speech shared on the internet, and that digital platforms must be held accountable for the content they help to disseminate.

“It is not possible that you can preach hate on the digital network, that you can do gun propaganda, teaching kids how to shoot, that’s what we see everyday,” he said.

Increasing security at schools is not enough to solve the problem, according to the president.

“We are not going to turn schools into maximum security prisons,” he said. “You can’t search children in schools. It would be pathetic for parents, for the mayor, for the governor, for the President, for the institutions of this country, for an 8-year-old child to have to show and open his backpack everyday at school.”

Lula also attacked social media and websites that profit from the proliferation of violence.

“The so-called big companies, which make money from the dissemination of violence, are getting richer and continue to publish lies.”

Read more: Man kills 4 children, injures 5 at Brazil daycare center

Monica Steffen Guise, Head of Public Policy for Integrity at Meta — which owns Instagram, Facebook and WhatsApp — called the speculation that the company would not take cases of violence seriously or that the company profited from disseminating hate speech a “myth.”

The director of government relations for Google in Brazil, Marcelo Lacerda, also stated that the company is collaborating with the government and that it has teams to identify, remove and report inappropriate publications.

Senator Damares Alves, who was a minister in the Jair Bolsonaro government, feels it’s important not to criminalize the platforms in order to generate prior censorship: “My concern with criminalizing social media is that later there will be censorship of the internet or even the press.”

According to lawyer and professor Marcelo Crespo, in Brazil there are systems of laws that apply to social media, but these laws do not allow the full control of the content shared on the platforms, making it more difficult to remove it in cases where false or abusive information is shared.

“What happens today is that the terms of use are not used correctly by big tech platforms, whether in photos, messages or videos,” Crespo told Brazil Reports. “They are responsible for controlling the content. The law has existed for about 10 years and, even so, there is still a lot of online crime and even the growth of abusive content sharing.”

Real vs online life

Supreme Court Justice and President of the Superior Electoral Court, Alexandre de Moraes, also took part in “safe school operation” talks, which included a meeting with President Lula on Tuesday.

Moraes has become a reference in Brazil for monitoring social media, as his role on the Electoral Court saw him combat fake news that was disseminated in the lead up to last year’s presidential elections.

At Tuesday’s meeting, Moraes defended the inclusion of an article in Brazilian legislation to make it clear that the rules of the real world must also apply in a virtual environment as well.

“The modus operandi of these aggressions and encouraged on social media in relation to schools is exactly identical to the modus operandi that was used against electronic voting machines and against Brazilian democracy. Social media still feels like no man’s land, a lawless land. We need to regulate this,” he said.

Moraes stated that, if there is no regulation, the encouragement to violent attacks will continue.

“A few years ago, the deep web spread these types of messages,” Moraes said. “The investigation was much more difficult because it was necessary to infiltrate people in that environment to reach those responsible. Today, this happens on normal social media. It’s on Twitter. You go to Google and teach a child how to make a bomb, and encourage him to repeat attacks that took place in the United States.”

According to Moraes, with a few proposals it would be possible to make “a great leap in quality” in Brazilian law. One of the measures the justice suggested is to provide more transparency about social media algorithms.

“Why, when we put ‘child’ and ‘attack’ in a search, instead of showing the news of the attack, it shows instructions on how to make a bomb? Why does one piece of news go ahead of the other?” he asked.

More than 7,000 complaints

The “safe school operation” task force also launched a channel where citizens can anonymously report threats of violence. In less than 20 days since its inception, 7,473 complaints have been filed on the Justice Ministry’s website, which led to the opening of 1,224 investigations.

In addition, 302 people have been arrested or detained on suspicion of involvement in alleged attacks. (In Brazil, adolescents under 18 cannot be arrested, just detained).

Another 694 teenagers were reportedly called to give statements to the police.

Read more: Brazil creates working group on violence in schools after 2 deadly attacks in 10 days

“When we look at a situation in which 302 arrests and detentions took place, this allows us, in a very eloquent and complete way, to measure that these are not isolated cases. In fact, it is a criminal and structured network that wants to recruit our youth for evil,” said Minister Dino.

For Cláudio Marson, a specialist in business consulting and auditing, the reporting channel is indeed an essential tool to improve security in schools:

“Since the reporting channel guarantees anonymity, it can create a safer environment so that students and teachers are not afraid to expose possible threatening situations,” he told Brazil Reports.