São Paulo, Brazil — Weeks after Brazilian officials announced a health crisis and a potential “genocide” on Yanomami indigenous land in the north of the country, over the weekend, Brazil’s newly appointed Minister of Indigenous Peoples, Sônia Guajajara, visited the area and said, “It is no longer possible for 30,000 Yanomami indigenous people to live with 20,000 gold miners in their territory.”

After her statement, initial reports indicated that over 300 miners had fled the territory, fearing legal consequences. But for four years, under the government of former President Jair Bolsonaro, miners were given free reign to do with the land (and the people living on it) whatever they pleased.

The result was gruesome. Over 570 children under five years old died from malnutrition and preventable diseases during that period and rivers in the indigenous territory are awash with poisonous mercury.

As more information becomes available about the devastation the Yanomami people endured in recent years, Brazil Reports spoke with indigenous rights leaders and anthropologists to understand the impact of the humanitarian catastrophe, the potential complicity of the Bolsonaro government, and how current President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva can help rectify the situation.

For the Yanomami people, years of degradation and neglect

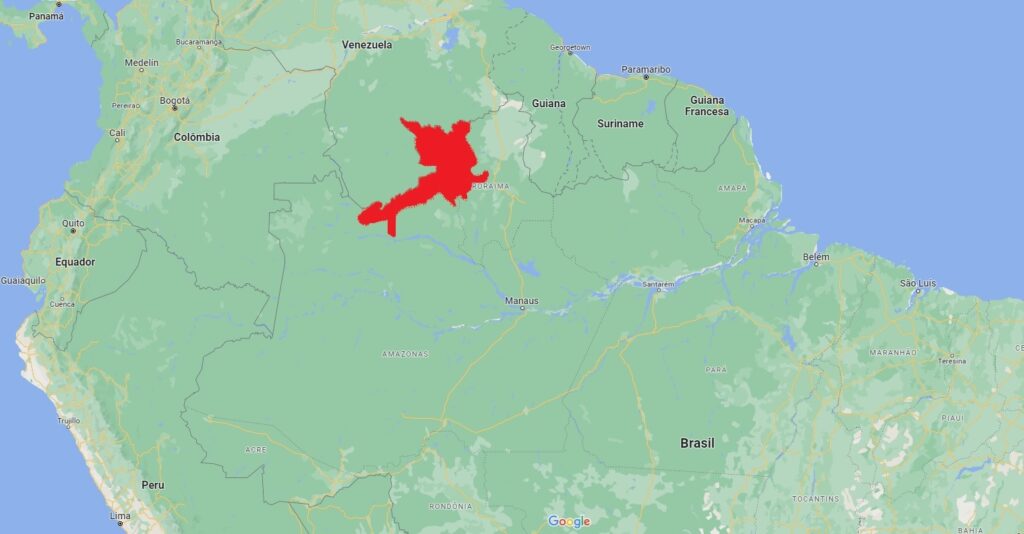

Although media outlets and activists had for years been reporting on and denouncing the worsening humanitarian crisis for the Yanomami people, who live on territory about twice the size of Switzerland in the northern states of Roraima and Amazonas that border Venezuela, it wasn’t until January when President Lula declared a health emergency and called what he saw in the territory “genocide” that the world opened its eyes to the severity of the situation.

Widespread hunger, disease and cases of violence have plagued the community for years.

Ministry of Health data released at the end of January show that approximately 36.5% of Yanomami children under the age of five are underweight to some degree. Of the 4,332 children the ministry reviewed, 586 of them had very low weight for their age and height, revealing severe malnutrition. Another 968 had low weight.

For specialists in the subject, such as Dr. Paulo Cesar Basta, with a PhD in Public Health, the malnutrition data among Yanomami children is grave and comparable to that of children in Sub-Saharan Africa.

Mercury, a toxic chemical that helps gold miners separate the valuable mineral from dirt and rock, is poisoning rivers where 378 different Yanomami communities fish.

By consuming the fish from these contaminated waters, or even swimming in them, the Yanomami people can develop a series of alterations to the nervous system causing motor and cognitive problems, vision and hearing loss, heart disease and even cancer.

“They are contaminating the rivers with mercury and consequently the fish, which is one of the staples of the Yanomami diet,” Priscilla Oliveira, a research officer at Survival International, a London-based human rights group, told Brazil Reports.

She said that in addition to poisoning the rivers, miners also bring with them “malaria, Covid-19, and other diseases” that can be severely detrimental to the vulnerable indigenous population.

Preventable diseases such as malaria have spread rapidly in the region. Data from the Ministry of Health show that in 2022, Brazil recorded 123,151 total cases of malaria across the country — 10% of which were registered within the Yanomami indigenous territory.

Infectious diseases such as the flu, pneumonia, and Covid-19, also impacted the population.

According to the Ministry of Health, 30% of Yanomami children under five who died in 2022 were killed by pneumonia. Other respiratory diseases, such as Covid-19, caused five deaths.

In addition to disease and starvation, the Yanomami people also suffered acts of violence carried out by miners and those sympathetic to their interests.

“There are cases of violence against women, such as rape, cases of violence against children, and on top of that, they also attack health centers [which serve the community],” said Oliveira.

In December, a Yanomami health care unit located in the Homoxi region was destroyed by a fire. According to the indigenous community, the fire was set by gold miners in response to a police operation carried out against illegal gold mining in the territory.

Last April, a 12-year-old girl from the Aracaçá community in northern Yanomami territory was kidnapped by armed prospectors and repeatedly raped. News of her death shocked the country and her murder has not been solved.

Lawyers are pressuring the International Criminal Court (ICC) to investigate Brazilian politicians, businessmen and security forces for crimes against humanity related to systematic attacks of land defenders.

Enock Taurepang is an indigenous leader and the coordinator of the Indigenous Council of Roraima, a state which is inhabited by the Yanomami people. He has long raised his voice to denounce atrocities against indigenous communities in Brazil, but he fears that sooner or later, his voice could be silenced like the 342 other land defenders that were killed in Brazil between 2011 and 2021.

“We make this complaint because we want it to stop, but there is a price on our heads,” Taurepang told Brazil Reports. “How are we going to survive an hour from now? There is no one to defend us, there is no one to protect us.”

The role of Bolsonaro’s government in the humanitarian crisis

Prospectors first laid eyes on the 9,664,975 hectares (about 23,882,673 acres) of Yanomami indigenous land (the largest indigenous reservation in Brazil) in the 1970s after a geological study by the Brazilian government indicated the potential for mineral wealth in the region, including uranium and gold.

According to Rogério do Pateo, a professor of anthropology and archeology at the Federal University of Minas Gerais, news of the mineral wealth spread fast, and by 1975, gold prospectors from across Brazil began to invade the area.

Over the years, the region began showing signs of degradation. Rivers were contaminated with mercury and the miners introduced diseases that whipped through indigenous communities.

In 1977, a measles outbreak killed 68 indigenous people. Later, in 1985, an outbreak of tuberculosis again threatened the population. It wasn’t until 1992, when the Brazilian government began demarcating Yanomami land, that the quality of life and security for the Yanomami people began to improve, Pateo told Brazil Reports. (Demarcation is the process of identifying, registering and drawing physical boundaries to protect indigenous lands.)

“It is not possible to say that there were no prospectors left, but they were small groups because there was even, in addition to the command and control mechanisms, a message that this would not be tolerated,” said Pateo.

That all changed, however, when Bolsonaro assumed the presidency in 2019.

“When the Bolsonaro government arrives, the message is: ‘We are going to open up the Yanomami land for mining,’” said Pateo.

According to the professor, Bolsonaro had long been on the side of miners, even drafting a bill as a deputy in the Chamber of Deputies in 1992 that would have revoked the Yanomami land demarcation.

“He is a spokesperson for these illegal miners who have been invading indigenous lands forever,” said Pateo.

“The gold miner is a human being like any other, he is a worker. My father panned for a long time. I got this habit from my father, I always carried a pan,” Bolsonaro said days after being elected.

As president, Bolsonaro spearheaded a number of policies that negatively impacted the environment and indigenous peoples including gutting the National Indian Foundation (Funai), the federal agency tasked with protecting indigenous peoples and demarcating their land.

He slashed funding for environmental protection measures, a move that ostracized him from the international community, and summarily fired protectors of indigenous rights and the environment at agencies such as Funai and the Brazilian Institute of the Environment and Renewable Natural Resources (IBAMA).

Under his watch from 2019 to 2021, an area the size of the country of Belgium was destroyed in Brazil’s Amazon rainforest.

“Before his election, his message was that he was going to hit Funai with a sickle,” said Taurepang, the indigenous leader from Roraima. “All the bodies that worked with the indigenous peoples, to defend the indigenous peoples and to take care of the indigenous peoples were scrapped. What he did was a genocide.”

In 2020, Bolsonaro’s government put forth a bill in Congress that would allow for mining on indigenous lands. The bill had many setbacks and was never passed during Bolsonaro’s time in office.

According to professor Pateo, Bolsonaro’s strategy shifted course after the legislative setbacks.

“If you cannot act in the sense of legally carrying out mineral exploration, what do you do? You destroy and dismantle the control mechanisms and send a message to everyone saying they can go in there because no one will be arrested, no one will be punished, there are no fines,” said Pateo.

In January, five civil organizations denounced Bolsonaro for genocide at the International Criminal Court (ICC), asking the court to open a criminal investigation into the president for failing to provide protection to the Yanomami people.

“I would not call this an omission, I would call it a conscious strategy by the Bolsonaro government to promote this genocide against the Yanomami indigenous people,” said Oliveira of Survival International.

In August 2022, The Intercept Brasil’s Carol Castro published a report that revealed that the Bolsonaro administration had ignored 21 requests for help from Yanomami people over a two-year period starting in 2020.

The messages, which contained details about attacks on the community by miners, were forwarded to the Federal Police, the military, and Funai. No response was given.

“The government was well aware of what was going on, what the scenario was and where it was going to go, and they did nothing,” Oliveira said.

Speaking from Florida, where he’s been since December 30, Bolsonaro downplayed the Yanomami health crisis, calling it a “farce of the left.”

He said his government carried out 20 healthcare initiatives in indigenous territories between 2020 and 2022, but did not specify where those actions took place.

Lula’s opportunity to rectify the Yanomami situation

In January, President Lula and members of his government visited the Yanomami territory and declared a state of emergency.

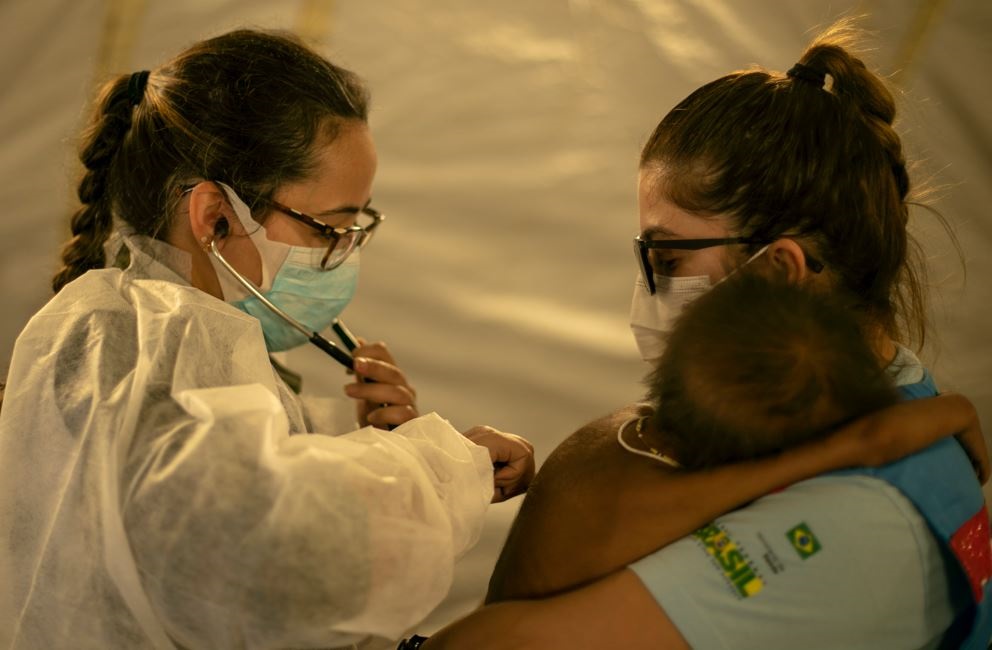

The Health Ministry set up a temporary Public Health Emergency Operations Center in the area to help address the most pressing issues.

In addition, over 30 tons of food have been delivered to Yanomami communities, and around 1,000 critically ill patients have been transferred to hospitals in Roraima’s capital, Boa Vista, by Brazil’s Air Force.

Last Saturday, Minister Guajajara returned to Roraima to observe the ongoing emergency operations, including efforts by the government to remove illegal miners from the region. According to reports, at least 300 land invaders have already fled Yanomami land.

“In order for us to get out of this health emergency situation, it is necessary to fight the root cause, which is illegal mining,” said Minister Guajajara at a press conference. “It is no longer possible for 30,000 Yanomami indigenous people to live with 20,000 gold miners within their territory, bringing this consequence of water contamination. So, the federal government in an articulated and interministerial manner, is already organizing actions for the removal of the gold miners.”

For Priscilla Oliveira, removing the prospectors is just one part of the equation. Keeping them from returning is the other.

She said that Brazil’s government must occupy the land and provide basic services such as healthcare to the communities, in order to keep illegal miners out of the region.

“Removal must be accompanied by the sending of medical teams and then, speaking in the long term, there has to be the installation of basic health units in the communities and the construction of security bases to permanently protect the land,” she said.

And for indigenous leader Taurepang, Lula’s recent creation of a Ministry of Indigenous Peoples is a good sign for the government’s dedication to their protection moving forward.

“[Lula] has already started taking out everyone who supported this, who covered up the crimes and started putting indigenous brothers [in strategic positions],” said Taurepang. “The Ministry of Indigenous Peoples itself is led by our sister Sônia Guajajara. Relatives know how to take care of relatives. We need a human person, who is able to see our pain and seek to end this pain, end the genocide that is happening within our territories.”