Bogotá, Colombia – A go-fast speedboat with three big outboard motors pulled into the muddy Orinoco riverbank deep in Venezuela and a guerrilla commander stepped ashore to greet the waiting community. Behind, a dozen or so troops, all uniformed and wearing military webbing, kept their guns ready.

After some greetings he approached me.

“You’re a long way from home,” I said, detecting a Colombian accent.

“Not as far as you,” he replied, with a smile. Fair point, as I am originally from London.

It was a rare moment of humor in an otherwise tense situation; the nearby villagers were clearly nervous of the guerrillas in their midst. But the commander was relaxed. He was patrolling the river, he said “at the invitation of the president of Venezuela, to protect the communities”.

The encounter was a surprise. Historically, Colombian rebel armies often flitted across 2,200 kilometers of porous land borders, seeking refuge from military attacks. They also controlled drug running, contraband and human trafficking between the two countries. But we were deep inside Venezuela; at least 1,000 kilometers downstream from the border.

Why would Colombian armed groups penetrate all the way to Venezuela’s Atlantic coast? And why would they claim to work for its president?

Some answers came this month in a report from investigators at Amazon Underworld who pieced together a terrifying picture of a humanitarian crisis taking place along the Orinoco River, much of it hidden from sight from international media.

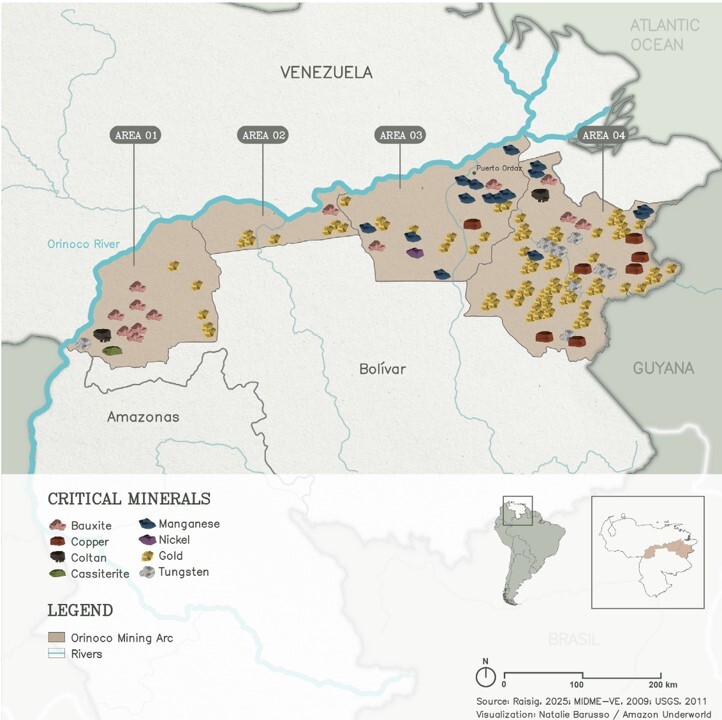

The global rush for critical metals had sparked a mining bonanza in high-biodiversity areas and indigenous territories, Bram Ebus, lead investigator of The Price of Progress: The Dark Side of Amazon Critical Minerals, told Latin America Reports this week.

Engulfed in violence

The region forms part of the Guiana Shield, which dates back more than 1.5 billion years and is geologically rich in critical and rare earth minerals such as tungsten, coltan, nickel and manganese.

But rather than map out these deposits and mine them in any controlled way, regional governments had allowed extraction to fall under criminal control, spawning an unholy alliance of illegal armed groups, state forces, corrupt officials and shady Colombian companies sending valuable ores to Chinese buyers.

Vulnerable communities were being trampled in the stampede, said Ebus, with reports of summary executions, enforced child labor, sexual violence, torture, disappearances, displacement and confinement.

The humanitarian crisis was most acute on the Venezuelan side of the border.

“Mining activities in Venezuela are engulfed in violence and illegality,” said Ebus. “Human rights violations are much worse there than in Colombia and Brazil, especially as state agencies do not interfere with abuses committed by armed groups that often work alongside state forces. Mines are run with an iron fist, and those who violate rules imposed, especially by Colombian guerrilla groups, face violence and even execution”.

Groups like the ELN (National Liberation Army) had established entire mining villages with their own power supply, shops and restaurants where miners could bring rare earth rocks in exchange for goods. The Colombian guerrillas either taxed local miners or ran their own mines. Witnesses also described Chinese buyers arriving by helicopter to check operations, according to the Amazon Underworld report.

The report also detailed how villagers who dared to challenge the armed groups – over access restrictions, for example – faced being locked up in makeshift jungle prisons where victims were kept for days with no food or water.

Locals accused of stealing were shot dead, and miners could be murdered for selling minerals to other buyers, according to witness accounts collected by Amazon Underworld.

Close collaboration

The mining free-for-all was transforming communities that traditionally sustained themselves through agriculture, fishing, and hunting. Many were becoming economically dependent on mining for survival, abandoning ancestral practices, and becoming reliant on costly river transport to bring basic supplies from distant cities.

Communities were also squeezed by the close collaboration between rebel groups like the ELN, ideologically aligned with the Caracas regime, and Venezuelan state forces such as the Bolivarian National Guard, who extorted miners for cash or minerals at military checkpoints – the hated alcabalas – or blockaded populations forcing them to work in the mines.

“At the entrance to the mines, at the control points, nobody can pass through, nobody leaves,” an indigenous miner told Amazon Underworld investigators.

Ebus said this collusion in the Orinoco belied recent claims by Caracas to be distancing itself from the Colombian rebels.

“In the mining areas, Venezuelan state forces have worked alongside Colombian guerrilla organizations, sometimes publicly appearing together in community meetings, with Colombian guerrilla members allegedly using vehicles of state agencies.”

His report also revealed cross-border collaboration with Colombian officials who assisted the smuggling of mined materials, often for fat kickbacks.

Rare earth ingots

The mined minerals left the Orinoco region by various routes, according to the Amazon Underworld report, but the majority were transported across the Orinoco River to Colombia then given faked documents to be shipped to China.

Investigators had identified collection points on the Colombian side where Venezuelan ores containing rare earth minerals were assayed by buyers, then falsified – often disguised as less valuable metals such as tin – and transported by river and road to Bogotá then on to sea ports.

In many cases, the minerals are falsely declared to be mined in Colombia, with companies going as far as to create phantom mines on Colombian soil to disguise their origin. More recently, Venezuelan ores were being smelted in Colombia to produce ingots containing tin and rare earth metals which could be flown direct to China.

The trade was enabled on the Colombian side by lack of legal regulations, and the machinery to test cargos, explained Ebus. State enforcement agencies sometimes seized suspect cargos – but then returned them to mineral traders after it was unclear what the ore contained, or what legal parameters were being broken.

“Colombia’s state agencies are painfully lagging behind organized crime in the critical minerals business and corruption is rampant. But at the central level, it’s not just corruption; it’s bureaucratic paralysis and a complete absence of adequate legal frameworks to tackle illegal extraction and trade,” said Ebus.

State surrender

The root of the problems was lack of effective state presence in areas of the Orinoco and Amazon river basins, a situation highlighted in a previous investigation by Amazon Underworld which found the presence of illegal armed groups in 67% of a total of 987 Amazon and Orinoco municipalities in six main countries.

State surrender to criminal enterprises had created an almost impossible task to claw back control over vast territories, with state militaries up against well-funded rebel groups now raking in new profits from rare earth metals.

The guerrillas I met in the mouth of the Orinoco had faster boats, more fuel, better guns, smarter uniforms and happier faces than their rag-tag counterparts in the Venezuelan national guard.

This was a point echoed by Ebus; with huge profits, and backed by powerful mercenary armies, the mining was not going away.

Solutions could stem from incremental technical improvements to detect deposits and control the flow of metals, he said. Proper assays at both extraction and supply chain levels could curb corruption and allow communities to better control mining in their own territories.

“Right now, miners are stripping topsoil just to see what rocks lay underneath, creating unnecessary environmental damage. They don’t even know what they’ve got,” he said.

A parallel strategy was to follow the money and identify the companies making vast profits from misery in the jungle. Regulation at export level would bring some control back down the supply chain.

The ultimate irony, said Ebus, was that this crisis was being driven by a global demand for critical minerals sparked by the boom in wind turbines, electric vehicles and solar panels.

“In the Orinoco and Amazon river basins, the extraction of the critical minerals needed for these green technologies is devastating indigenous communities and vital ecosystems — all the while fuelling guerrilla violence,” Ebus concluded.

Featured image: A fragment of mine soil rich in critical minerals.

Image credit: Bram Ebus, co-director, Amazon Underworld