Four days before the death of student protester Dilan Cruz – who succumbed to injuries suffered from the impact of a tear gas canister being launched at his head by anti-riot police in Bogotá, Colombia – sparked nationwide outrage, two young men were gunned down by security forces during the country’s national protests over 500 kilometers away in the port city of Buenaventura.

Spare some coverage in local media, their deaths have mostly gone unreported.

According to official communiques, interviews with officials close to the investigation, and statements from witnesses made to Latin America Reports, on the evening of November 21, a crowd of protesters gathered in front of one of the city’s largest shopping malls, Viva Buenaventura. It has been reported that some of the people gathered were attempting to loot the mall when security forces arrived.

Clashes erupted with protesters throwing rocks at security forces which included members of the local police as well as the Colombian Naval Infantry. (According to officials close to the investigation, Colombia’s anti-riot police, which carry non-lethal weaponry, were not present at the scene).

The security forces opened fire, using what officials described as high-powered weaponry, resulting in the deaths of 22-year-old Wilber Mina Lizalda and 17-year-old Brayan Alexis Vargas Gomez. A member of the police and the Naval Infantry were also injured, according to a press release from the Colombian Navy.

Read: Excessive police violence in protests cause deaths and thousands of injuries

Both of the deceased were shot in the back, according to an official who asked to remain anonymous because the investigation is ongoing.

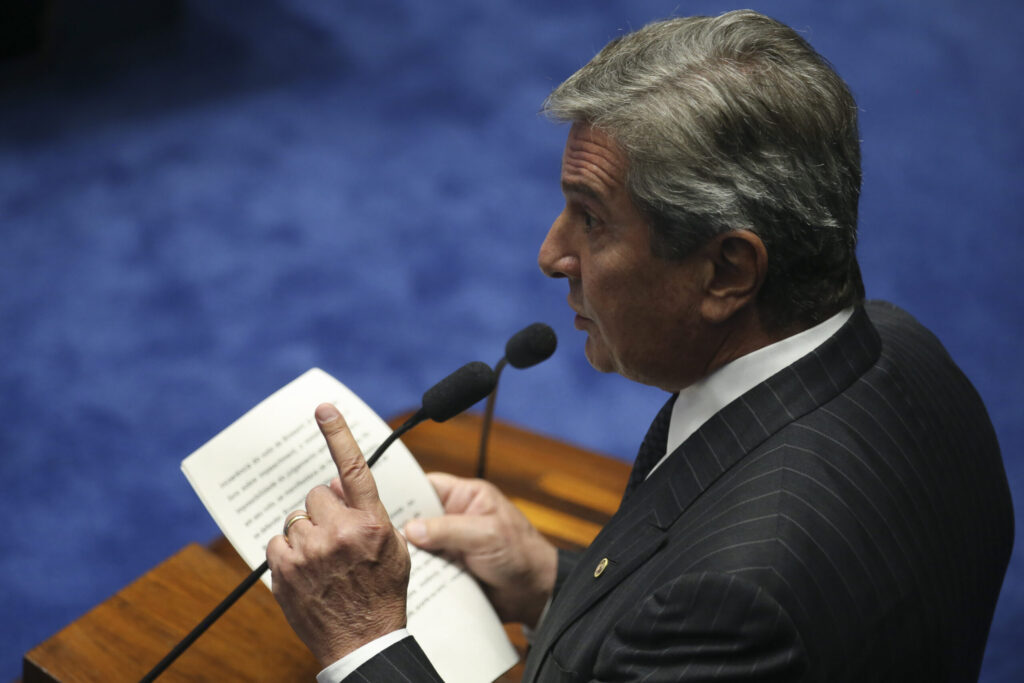

Mr. Wilber Mina Lizalda, Credit: Facebook

Just a two-minute walk from Viva Buenaventura mall, down a steep, dusty, gravel road, there’s a shanty town where Mr. Mina lived with his mother, step-father and two of his siblings. Sitting near the entryway weeks after her son’s death, Mrs. Elizabeth Lizalda Palacios says, “I keep thinking he’ll come in the door … come into my room … and give me a hard time about losing weight like he always used to tell me.”

The two were very close, even for a mother and son. Mr. Mina worked with his mother selling fruit in the city center. According to her, he was a fan of the Real Madrid soccer club, liked to go out dancing with friends, and adored his nine-year-old sister as well as his dog — a scraggly dachshund mix that kept peering up from behind its over-sized food bowl as we spoke.

According to an official close to the investigation, Mr. Mina had no prior criminal convictions.

On November 21, the day of the first national protests, Mr. Mina left his home at 6:00 PM, according to his mother. She gave him a call at 9:30 PM when he hadn’t returned home. “Mom, I am here at the [Viva Buenaventura mall] waiting for a girl,” Mrs. Lizalda says he told her. She warned him that things could get dangerous there as the protest progressed.

A few minutes later, Mrs. Lizalda heard bursts of gunshots ring out from blocks away. Minutes after that, Mr. Mina’s brother received a phone call and left the home with his step-father. When he returned shortly after, said Mrs. Lizalda, he stopped in the doorway and sobbed. “Something happened to Wilber!” Mrs. Lizalda recalls crying out.

She said she made her way up the hill, two minutes walking to the mall, where she saw her son lying lifeless on the pavement.

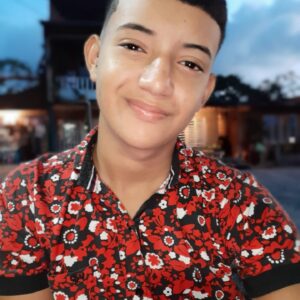

Mr. Brayan Alexis Vargas Gomez, Credit: Facebook

Two months after Brayan Alexis Vargas Gomez turned 17, he moved from his small town of Pitalito, Huila to Buenaventura, a 12-hour journey by bus. He followed his best friend and his best friend’s wife (who is also Mr. Vargas’ sister) to the port city to work in a bakery.

“His boss told me he was always very respectful,” Mr. Vargas’ mother, Deicy Gomez, told Latin America Reports in December while sitting in the home of the owner of the bakery where her son worked.

A hard worker, kind and always smiling, is how Mrs. Gomez described her son who she said was also her best friend. Although they were apart, Mrs. Gomez would speak to her son daily on Facebook Messenger where he’d send her videos of himself playing soccer with friends in his adopted neighborhood. And in October, he sent for his mother and surprised her with a vacation to a nearby beach as her birthday gift.

According to an official close to the investigation, Mr. Vargas had no prior criminal convictions.

On the evening of November 21, Mr. Vargas and his friend and co-worker at the bakery (referred to by the pseudonym Charlie because he is a witness in an ongoing investigation) were settling in for the night when a mutual friend knocked on their door.

“Hey, let’s go to [Viva Buenaventura mall], there’s a lot of people gathering,” Charlie recalled their friend saying during an interview with Latin America Reports in December.

Shortly after arriving at the protests in front of the mall with Mr. Vargas, Charlie recalled that protesters began throwing stones. “Everyone began to run in all directions,” said Charlie. During the confusion, a burst of gunshots rang out. “I told him: Brayan run … Brayan run!”

Charlie said he quickly lost sight of Mr. Vargas.

Turning around to head back toward where he last saw Mr. Vargas, he said he heard people screaming, “They shot a child, they shot a child!” (A video posted to social media allegedly depicts this moment).

Charlie recalled seeing Mr. Vargas lying on the pavement, with a member of the security forces about 10 meters away. “Whoever throws rocks, we’ll shoot,” Charlie alleged the member said. Charlie yelled out for people to stop throwing rocks as he bent down to take Mr. Vargas in his arms and apply pressure to his wound. “He was dead I think … He didn’t speak, he didn’t move.”

A Forgotten City

Despite being the 12th most active port in Latin America and the Caribbean and generating 27% of Colombia’s import tax revenue, the people who live in the port city of Buenaventura have been forgotten.

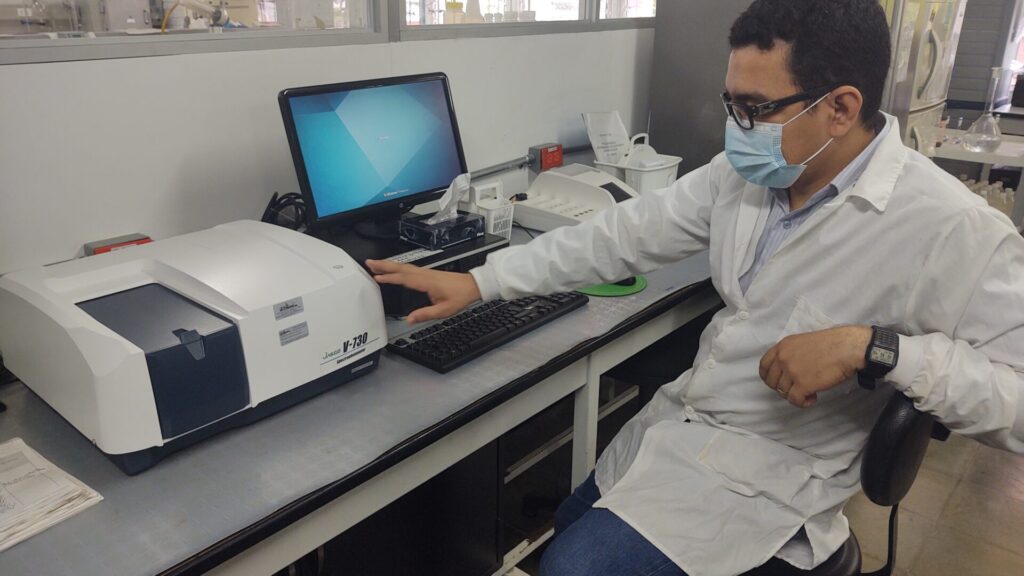

Barrio La Playita, Buenaventura. Credit: Jim Glade

Two thirds of the city’s 400,000 residents live in poverty; unemployment exceeds 65%; potable water is only available for most residents for just eight hours each day, and a new high school hasn’t been built in the city in 44 years. To boot, extreme violence has bedeviled the region for decades as illegal armed groups vie for control of lucrative drug shipment routes.

Residents said that there hasn’t been nationwide outrage surrounding the deaths of the two young men because the rest of Colombia has forgotten about Buenaventura.

“Look at the boy from Bogotá that was killed by [Colombia’s anti-riot police]. How many news stories have been written about him?” asked Mrs. Lizalda in her living room. “How many people have spoken out against his death? But for the two boys who were killed in Buenaventura, nobody has spoken out. . . Let’s raise our voice. Raise our voice Colombia.”