Yesterday, March 14, marks a year since Rio de Janeiro city councilwoman and human rights activist Marielle Franco was murdered in a planned assassination that also took the life of her driver, Anderson Gomes.

Although the investigation into who ordered her death remains unsolved, recent developments revealed days before its one-year anniversary have seen two individuals arrested on suspicion of her murder. Élcio Queiroz and Ronnie Lessa, now detained, were former police and military police officers respectively. Queiroz had previously been expelled from the police for corruption.

Another line of suspicion links Franco’s killers to organized crime militia group Escritório do Crime, which engages in extortion activities and controls certain favelas in Rio’s West Zone, as well as illegal activities that occur within them. Rio’s militias are largely composed of ex-military policemen and have also been linked to extrajudicial executions.

Throughout her political career, Franco publicly campaigned for the human rights of Brazil’s marginalised groups: a fight that often contradicted the interests of some of the most powerful criminal organisations in the country. As a female, bisexual, Afro-Brazilian single mother who was born in Rio’s Maré favela, she embodied each of these communities.

“She was the voice of favela residents against their oppressors, against militias, against inequality imposed by public power,” Franco’s personal friend and fellow city councillor David Miranda told Brazil Reports in 2018.

“I am sure it was a political crime, committed by those who wanted to silence Marielle,” he said.

Last year, Franco’s supporters relentlessly campaigned to pass the legal projects she had been unable to complete, which focused mainly on rights for Afro-Brazilian women, mothers, young people and the LGBTQ community.

Her death also inspired over 1,000 Afro-Brazilian women to run for office in last year’s presidential elections, a 60% increase over the previous election cycle according to Americas Quarterly. Although many were not elected, Mônica Francisco, Dani Monteiro and Renata Souza, Franco’s former chief of staff, were appointed Rio state legislators in January 2019.

Outside of Brazil, Franco’s murder also had international repercussions for those who shared her vision. Personally “moved and outraged” by her murder, Portuguese artist Alexandre Farto was approached last year by Amnesty International and Franco’s partner Mônica Benício to construct a mural in her memory.

Marielle Franco | Brave Walls initiative | Scratching the Surface project | Lisbon. Image courtesy of Natacha Cabral.

The mural’s purpose is to “celebrate the life of someone who was, and continues to be, a great inspiration,” Farto told Latin America Reports. “On the other hand, it helps to ensure the continuity of the causes she defended throughout her life…and keeps her case present, in order to bring [the perpetrators] to justice.”

Franco’s partner Benício has consistently been at the forefront of the campaign, ensuring her legacy lives on and demanding justice for the woman she was due to marry this year. Besides gaining the support of human rights organisations such as the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, Amnesty International and the United Nations, Benício has also been the face of protests across Brazil demanding answers as to who ordered Franco’s killing.

Most recently, she led an award-winning procession organised by Rio-based samba school Mangueira that took place during this year’s carnival. The parade paid tribute to Afro-Brazilian and indigenous human rights defenders persecuted throughout the country’s history, including Franco.

Image courtesy of @heldersalomao – Twitter.

Speaking to Latin America Reports, political sciences professor at Rio’s Universidade Federal Fluminense Carlos Serra explained why he believes that the current government is perpetrating continued levels of violence and attitudes of hatred towards minorities in Brazil.

“It seems as if President Bolsonaro is still campaigning. He governs in an underground way…still through social media…through these followers that are becoming increasingly sectarian, that encourage hatred, intolerance and violence, particularly in relation to minority groups,” he said.

In line with global trends, levels of violence against marginalised groups in Brazil have indeed continued to worsen since the inauguration of Brazil’s new president. For example, after Bolsonaro removed the LGBTQ population from national human rights directives at the beginning of this year, openly gay congressman Jean Wyllys, who received death threats, decided to quit his job and leave the country. Gender-based killings also continue to be a concern, claims a recent IACHR report published in February 2019, revealing that 126 femicides had taken place since in Brazil the beginning of the year.

“Marielle unfortunately…represented everything that this political group hates,” political sciences professor Serra pointed out, referring to the Bolsonaro administration.

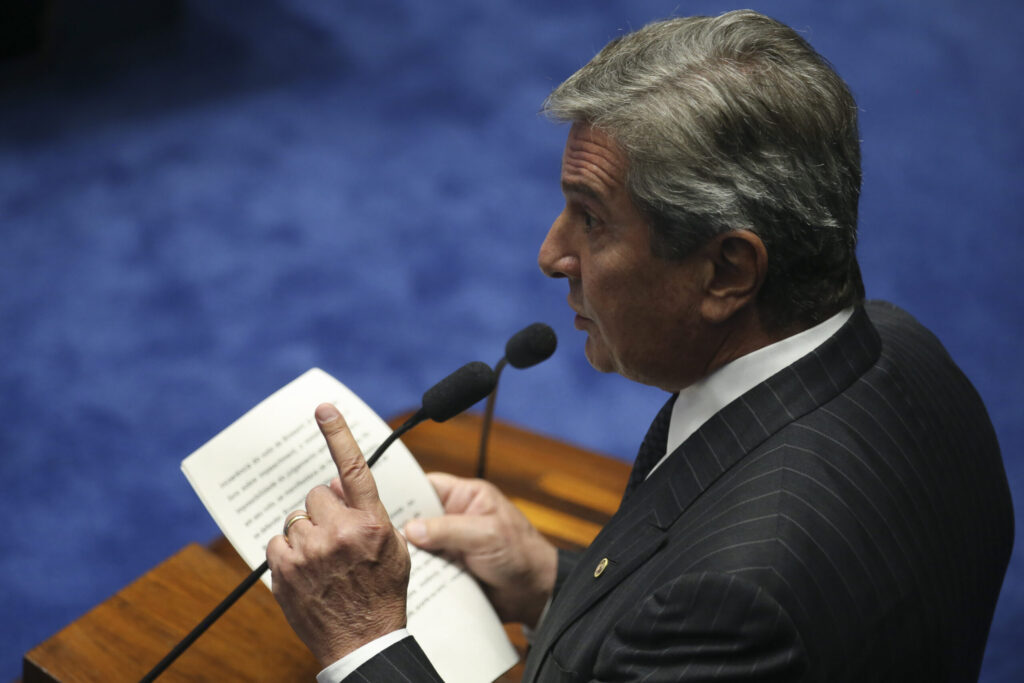

During Bolsonaro’s electoral campaign last year, federal representatives Rodrigo Amorim and Daniel Silveira who have since been elected from his political party (PSL), publicly destroyed a road sign plaque that had been installed in Franco’s memory, claiming it to be their “civilian duty.” According to Brazilian daily O Estado de São Paulo, their actions were endorsed by Bolsonaro’s son, senator Flávio Bolsonaro.

Uma imagem que diz tudo. pic.twitter.com/iKHrXaBGCQ

— Gregorio Duvivier (@gduvivier) 3 October 2018

More recently, when reporters asked the Brazilian president who had ordered Franco’s murder, he replied, “I’m also interested in finding out who ordered my murder,” referring to the assassination attempt he suffered at a campaign rally last year.

Within the past week, the Bolsonaro family’s relationship with those convicted of Franco’s murder has been thrown into the spotlight after a photo of the president with murder suspect Queiroz began to circulate on social media. Police forces also confirmed rumours that one of Bolsonaro’s younger sons was romantically involved with the daughter of second suspect, Lessa, who coincidentally also lived in the same Barra da Tijuca condominium complex as the president.

“The worst photograph in Jair Bolsonaro’s life” https://t.co/68EhLA9VTn This image is starting to circulate in Brazil. It appears to show Brazil’s far right president with 1 of men arrested this morning for #MarielleFranco murder pic.twitter.com/KMns2EbqVy

— Tom Phillips (@tomphillipsin) 12 March 2019

Although these findings have been dismissed as mere coincidence, all eyes are now firmly fixed on the Bolsonaro family and its relationship to militia groups linked to Franco’s murder. With concrete proof that his son, Flavio, employed both the mother and wife of the alleged Escritório do Crime leader, suspicions that the president is attempting to obstruct her legacy remain higher than ever.