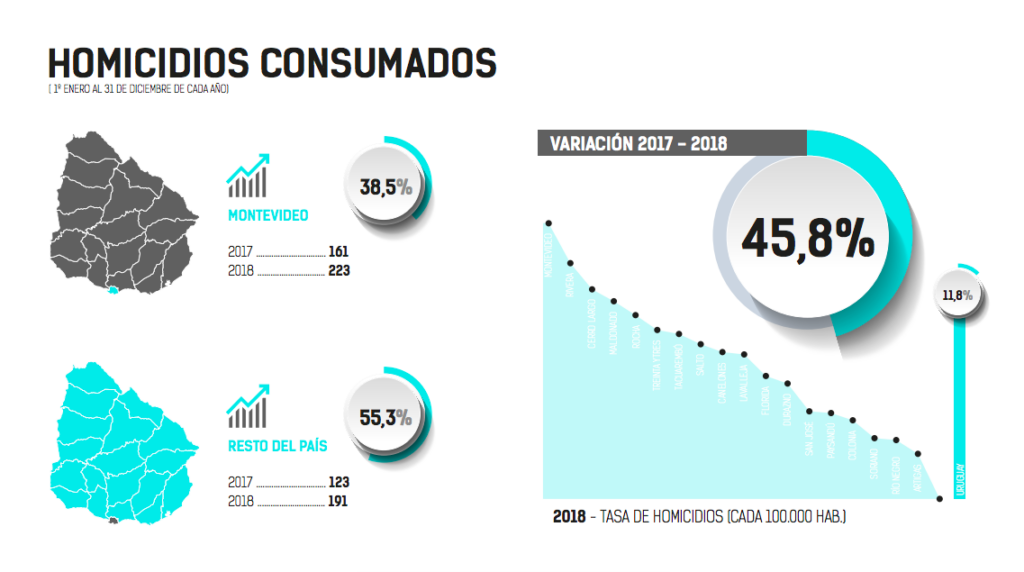

Last month, the Uruguayan government revealed that homicides in the country rose 46 percent in 2018. This drastic rise corresponds with increased public support for tougher policies against crime, and is likely to play a leading role in the upcoming presidential campaigns.

The death toll in 2018 was 414, up from 284 the previous year. This means that the official rate of homicides in Uruguay reached 11.8 per 100,000 inhabitants, the highest in the country’s history.

The government’s data shows that the number of gun-related homicides in particular has increased, from 170 in 2017 to 296 the following year, whereas non-gun-related murders have only increased by five counts. Violent crimes have also risen dramatically in comparison to 2017, with a 53.8 percent rise in aggravated robberies.

The government affirmed that the majority of the counted deaths (47 percent) occurred within organized criminal groups and drug traffickers.

This last piece of information is key in understanding why the level of murders has risen so quickly in such a short time.

Following the same trend as in the past decade, the majority of these crimes took place in the capital, Montevideo. However, Frank Mora, Director of the Kimberly Green Latin American and Caribbean Center (LACC) explained in The Global Americans that other regions have also recently suffered a disproportionate number of homicides.

Small towns bordering Brazil, such as Rivera and Chu, have had increasing levels of violent crime, he wrote, and they have become hubs for smuggling drugs; counterfeiting goods and alcohol; activities led by criminal gangs and which have had a direct effect on public security.

In these areas, homicides in 2017 reached 13.5 per 100,000 in Rivera and 11.8 per 100,000 in Chu, much higher than the year’s average of 8.1.

However, the criminal groups that exist in Rivera and Chu aren’t necessarily growing, Eduardo Bonomi, Uruguayan minister of the interior, assured in an interview with El Observador.

“[We] are convinced that the rise in violence in Uruguay is not a product of the strengthening of criminal groups, but rather confrontations between them,” he told the Uruguayan paper.

Regardless of the root causes, the rise in homicide has caused increasing pressure from the Uruguayan public to implement harsher security measures. In response, prospective presidential candidate Jorge Larrañaga created a petition called “Live Without Fear,” which called for a referendum to implement harsher security policies.

In February, he presented the petition to the Uruguayan Senate with over 400,000 signatures, thousands more than the minimum needed to pass the measure.

The referendum will take place in October, the same month as the presidential elections, and in March public opinion consultant Opción showed that 67 percent of those surveyed were in favour of harsher policies against crime.

Public security is expected to play an integral part in the upcoming elections. In May 2018, Opción revealed that 74 percent of Uruguayans agree that the military should work with the national police force in matters of public security.

Mano dura (iron fist) policies are also being rolled out across the continent, namely in Mexico and Brazil, where the local governments are creating militarized police forces in a bid to reduce violent crime, despite evidence that it isn’t effective. It is up to Uruguayans to decide if they will follow their Latin American neighbours in public security policies or try a different tactic.

Read more about gun violence in Latin America: